COL. JAIME

C. VELASQUEZ

1907 – 1979

“Duty, Honor and Country”

“Duty, Honor and Country”

“On July 4, 1946, Independence Day,

Col. Jaime C. Velasquez decided uncompromisingly to retain his Filipino

citizenship, notwithstanding the offer of U.S. citizenship by the United

States.”

“Makati’s, residential villages, hotels,

malls, offices, and restaurants, are a testament to Jimmy’s vision of a

commercial and residential complex thriving in a balanced environment.”

BALIWAG

When the United States took

over the Philippines in 1898, ending three centuries of Spanish rule, the

Americans had to find a way to bridge the “communication gap” between them and the Filipinos. Since Baliwag, Bulacan was the first

municipality organized under the American regime, it was here that the

Americans established the first public schools with English as the sole medium

of instruction. Up to this time, the

Filipinos had been using only sign language in talking to the Americanos. Education was compulsory, and children who

played hooky had truant officers to reckon with.

In this setting Jaime C. Velasquez was born on April 4,

1907 in the town of Baliwag, province of Bulacan, the third child in a family

of four of Juan Velasquez and the former Maria Camacho. The Velasquezes

lived on Mariano Ponce Street, a community of well-to-do folk who tended their

own farms. “Emeng” picked up an academic

bent and a fondness for books from some of his relatives who were school

teachers in Baliwag.

After finishing primary and intermediate schools in Baliwag, where he graduated valedictorian,

Jimmy attended U.P. High School in Manila, graduating valedictorian once again

in March 1924. During his first year in

Pre-Medicine at the University of the Philippines in late 1924, he took the

entrance exam to the U.S. Military Academy on a dare. The result - He was appointed by Major General Leonard Wood, then

Governor General of the Philippines, to the United States Military Academy at

West Point. He would be a “pensionado”,

a government scholar.

Standing l to r: Pepe, Anita,

Jimmy Sitting l to r: Maria, Juan. Sitting on floor: Maning

Baliwag,

Bulacan just before Jimmy left for West Point, August 22, 1925

Medicine was his career of choice,

perhaps a heart surgeon, perhaps a brain surgeon. But that was years away.

Though his family was more than comfortable in Baliwag, those years would

cost his hard working farmer father a good part of his savings. After topping the West Point entrance exam

in the fall of 1924, and thereby earning the privilege of entering this

prestigious American institution, Jimmy made the heart-wrenching decision of

accepting the appointment, knowing he was saying goodbye to a career in

medicine. Filipino cadet Jaime C.

Velasquez made that lonely month-long boat trip alone from Manila to San

Francisco, then a week by train to New York, and entered West Point with the

Class of 1929 in September 1925.

WEST POINT

At West Point, Jimmy had no problems

with the academic demands of the illustrious institution. He was interested in Math and Science, and

those subjects came easy to him. His

problems came with the physical demands of military training. No, he was not weak. Quite the contrary, he was a strapping 5’11

athletic type and built like a boxer.

But asthma ran in his family, and the harsh winters exacerbated his

allergies, which caused him to be sick often, especially in his first

year. His weak respiratory constitution

made the physical demands of a cadet harder on him than on the others.

In the summer of 1926, he stayed

alone in the New York area, recuperating from the physical demands of being a

Plebian (freshman) at West Point. And

unlike other American cadets who went home for the summer, he felt it would be

wasteful to make that month-long trip back to the Philippines and then back

again to the U.S., all within 3 months.

It was a lonely life.

In the summer of 1927, he decided to

be more adventurous, by going on a trip visiting different countries in

Europe. While on that trip, his health

started to deteriorate, which caused him to cut his trip short. Back at West Point, a physical examination

revealed that he had tuberculosis, which at that time, was generally accepted

as fatal. He was immediately placed on

sick leave, and sent to Fitzimmons General Hospital in Denver, Colorado to

recuperate.

He spent nearly two years at the

hospital, not knowing if he would ever be well enough to resume his studies at

West Point. But with his fighting

spirit, a firm determination to get well, and the excellent medical attention he

received at the hospital, Jimmy overcame the disease. It was now the summer of 1929, and his classmates at West Point

had graduated ahead of him. In August

1929, he was pronounced to be completely cured of tuberculosis, and was allowed

to join the Class of 1931.

When he returned to West Point in the

Fall of 1929, he pursued his studies and activities with renewed vigor. Ever confident in speech and demeanor, which

is unusual for a Filipino studying in an American institution, Jimmy excelled

in oratory, and led a West Point debating team in a competition in Europe. He graduated from West Point in June 1931

with a major in Electrical Engineering, with a rank of #17 out of a class of

142, earning a total of 2,696.04 out of a maximum possible 2,970.00 General

Merit points, a merit system that measured both academic standing and physical

prowess.

JAIME CAMACHO VELASQUEZ

WEST POINT 1931

“Jimmy is a man who came down to us from

the class of ’29. And it has been a stroke

of good luck for us to have him with us, although it came as a result of one of

the toughest breaks a man has ever had.”

“If determination and perseverance was ever

combined in one man and coupled with a grip of iron, they were incorporated in

Jimmy. The change of climate from the

Philippines to West Point tore down his health completely, but it never

destroyed his determination.”

THE PHILIPPINE CONSTABULARY

After graduating from West Point in

1931, he was promoted to second lieutenant and was commissioned an instructor

at the Philippine Constabulary Academy at Camp Henry T. Allen in Baguio

City. He also managed to qualify for a

Foreign Service credential with the accolade of Starman, of which there were

only five from the meager seventy that earned their credentials between 1914 to

1990.

At that time, the Philippines was

divided and organized into ten military districts. Jimmy was assigned Assistant District Commander of the 10th

Military District, which comprised of the island of Mindanao and the Sulu

Archipelago. He assisted in the

organization and establishment of the district headquarters, and of the camps

and stations for the training cadres of the district. In late 1935, Jimmy returned to Manila to serve as Chief-of-Staff

of the Philippine Army, and as Secretary to the Philippine Army General Staff.

In 1938 he revisited the United

States as a student at the Infantry School, Fort Benning, Georgia, Class of

1938, and at the Command and General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, Class of

1939. Upon his return to the

Philppines, Jimmy was appointed Commandant of Cadets, Philippine Military

Academy. The Philippine Constabulary

Academy where he taught after his graduation from West Point was converted in

1936 into the Philippine Military Academy, patterned after the U.S. Military

Academy at West Point.

THE PHILIPPINE COMMONWEALTH

On July 10, 1934, in what probably

was the most orderly and quiet election in the history of the country to date,

the Filipino people elected 202 delegates to the Consitutional Convention. The purpose of the Constitutional Convention

was to frame a constitution that would be consonant with the nationalism and

aspirations of the Filipino people.

The framers of the Constitution,

cognizant of the needs of the people and aware of the lessons of the past,

approved provisions that were strongly nationalistic in character. Manuel L. Quezon, then the Senate President,

believed that the Commonwealth should be established on a non-partisan basis,

for the cooperation of the majority in the legislature was needed in solving

serious economic and social problems in the country.

For most of his public life, Manuel

L. Quezon had fought the United States vigorously for the speedy independence of the Philippines. He played a

major role in obtaining Congress passage in 1916 of the Jones Act, which

pledged independence for the Philippines without giving a specific date when it

would take effect. The next step was to pin down the United States for a date

when independence would be granted.

This led to the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which Quezon fought

hard for, and which the U.S. Congress passed under President Roosevelt to provide

guidelines in the winning of independence for the Philippines within 20

years. Unfortunately, this Act required

certain provisions that were difficult for Filipinos to accept – Granting

American citizens in the Philippines rights equal to those of the Filipino

citizens; and, recognizing the right of the United States, pending her complete

and final withdrawal from the Philippines, to control all matters pertaining to

the latter’s currency, trade, immigration and foreign affairs. Instead of fighting the U.S. on these

provisions, Quezon urged that Filipinos work with the U.S., since the priority

was the granting of independence.

Differences in the provisions could be worked out after independence was

granted.

Jimmy followed these events with

great interest, as he performed his duties as Assistant District Commander of

the 10th Military district.

He admired Quezon’s nationalistic fervor, and agreed with his practical

approach to dealing with the United States on the issue of independence.

On November 15, 1935, the

Commonwealth was inaugurated with Manuel Quezon and Sergio Osmena as its

president and vice-president, respectively.

The reins of government, with the exceptions of the currency and foreign

relations, were now completely in the hands of Filipinos. The government just launched, Quezon

declared in his inaugural address, was only “a means to an end. It is an instrument placed in our hands to prepare

ourselves fully for the responsibilities of complete independence.”

In 1940, Jimmy served as Regimental Executive at Camp

Parang, Cotabato, Mindanao. By that

time, he had married the former Nieva Eraña, who made the trip with him to Cotabato. Life was hard at Camp Parang, where the

weather was uncomfortably humid, where life’s amenities were sadly lacking, and

cleanliness a luxury. Mosquitoes thrived in this environment, and diseases

carried by these mosquitoes were a constant threat. Tragically, Nieva lost her life to a serious bout with malaria

within less than a year after they arrived in Cotabato. Devastated, Jimmy wound down his affairs at

Cotabato and returned to Manila to decide what to do next.

A few months after his return,

President Quezon called, asking Jimmy if he would serve as his aide-de-camp. There were continuous threats to the

President’s and his family’s safety, and they needcd someone of Jimmy’s

experience to provide them personal security while in public or while

traveling. Jimmy needed no

convincing. Here was his chance to work

closely with man he greatly

admired. In 1941, Jimmy accepted an

appointment as aide-de-camp to Commonwealth President Manuel L Quezon. As it turned out, this appointment saved his

life during World War II.

Lt. Col. Jaime C. Velasquez, (standing second from

left), aide-de-camp to President Manuel L. Quezon, with the Quezon family and

friends, Saranac Lake, New York, 1943

WORLD WAR II

In December 1941, Jimmy’s division

fought the Japanese in central Luzon, and helped insure the orderly withdrawal

of the South Luzon Forces to the Bataan Peninsula. At Bataan the Division repulsed repeated Japanese attacks against

the western flank of I Corps under the command of Major General Jonathan

Wainwright. About three weeks before

Bataan fell and at the request of President Quezon, Jimmy was relieved of his

duties as Chief of Staff, 91st Philippine Army Division and

appointed as his aide-de-camp. Jimmy

accompanied President Quezon and his family in their escape from Corregidor to

Mindanao, then to Australia, and on to the United States. Had he not been appointed, he would have

stayed in the Philippines, and possibly captured by the Japanese, who were

looking for him.

Jimmy never knew the hell that was Death

March for he was among the lucky ones who had escaped to the U.S. via

Australia. To his dying day he believed

that his escape from Bataan was no big deal, that the real heroes are those who

stuck it out in the Philippines. He

remained deeply grateful to his older brother Pepe, who was tortured by the

Japanese because of him. They wanted to

know Jimmy’s whereabouts but Pepe refused to tell them.

After he was released from his

duties as aide to President Quezon, Jimmy took a three-month Battalion

Commander and Staff Officer Course at the Infantry School, Fort Benning

Georgia. Then he joined the First

Filipino Infantry Regiment which was organized, equipped and trained in the

West Coast. He was one of the battalion

commanders in the New Guinea and Southern Philippine campaign. At New Guinea, Jimmy was within a few feet

of death when his battalion sustained a Japanese attack that killed many of his

men. He splattered himself with mud and

blood from the dead men around him, and lay motionless as the Japanese walked

past them.

Thereafter he served successively as

assistant G-2, U.S. XI Corps, and as assistant G-2 of General Walter Krueger’s

Sixth U.S. Army during its operations against the Japanese in Southern and

Central Visayas, and in Southern Luzon.

After the Liberation of Manila, Jimmy was appointed Deputy Commander,

Military Police Command, Army Forces Western Pacific, and subsequently as

Provost Marshal General, Philippine Army.

With a combination of hindsight,

national fervor and a dash of calculated risk, Velasquez had moved for a

transfer from the United States Army to the Philippine army at some fair cost

to his rank – From full colonel status, he was relegated to lieutenant colonel. War reparations were the order of the day,

and much had to be done. Velasquez was

anxious to serve his country at a time when the Philippines needed help in

rebuilding after the war.

Wedding of

Col. Jaime C. Velasquez

&

Theresa LaO

May 11, 1946

On July

4, 1946, the Philippines was finally granted full Independence. On exactly that day, Col. Jaime C. Velasquez was

placed on inactive status by the U.S. Army, having uncompromisingly decided to

retain his Filipino citizenship, notwithstanding the offer of U.S. citizenship

by the U.S. Government. The newly independent Philippine government, however,

restored him to active duty and commissioned him as a Colonel in the Philippine

army. In May 1946 he had married the

former Theresa LaO, daughter of Pacita Arguelles and Gabriel LaO. With foreign service colors tucked under

his sleeve, Jimmy was immediately commissioned by the newly elected President

Manuel Roxas as the Philippines’ first Military Attaché at the newly

established Philippine Embassy in Washington D.C., as well as Chief-of-Staff of

the Philippine Service Command. The

newly weds left for Washington D.C in October 1946. While on this assignment, he participated in the negotiation of

the Mutual Defense Assistance Pact between the Philippines and the United States. In 1950 Jimmy returned to the Philippines

and, after a short stint as Chief of Staff, Philippine Service Command, he

retired from military service in 1951.

President Truman signs the

National Defense Assistance Pact between the Philippines and the United States

– 1948. Standing l to r: Al Valencia - Press Attaché, Narciso Ramos

(father of Fidel V Ramos), J. “Mike” Elizalde - Philippine Ambassador to the

U.S., O’Neal – U.S. Ambassador to the Philippines, Ramon Magsaysay, Congressman

Atilano Cinco, Col. Jaime C. Velasquez

AYALA

The liberation was as much an upheaval as the Japanese Occupation that

preceded it. Major portions of Manila

were razed by fires or had collapsed under the heavy bombing. Many were displaced and a devastated

countryside was rife with unrest.

Makeshift shelters were hastily erected as millions of refugees flocked

in from the provinces. The City, once

inhabited by 450,000 residents in the Peacetime era, had ballooned to 1.5

million residents in a single year.

At that time, Hacienda Makati was an

estate that stretched along the Pasig River across the old Spanish

governor-general’s summer residence in Guadalupe. It rolled downstream along the western bank of Sta. Ana, and

swept across the fields of Olimpia, San Andres and Singalong extension. Makati was a vast, raw expanse where share

croppers cultivated rice and horse fodder.

In the early 1920s, large

unproductive portions of this land were parceled into small residential lots

and offered at nominal cost. These

early districts were characterized by narrow sreeets, poor drainage and few

public amenities, but the lots sold well nevertheless. By the end of World War II, the hacienda had

dwindled to little more than 930 hectares and brought a quandary to its owners,

Ayala & Compania.

The havoc of the war leveled

practically most of the residential areas in Ermita, Malate and other bayside

neighborhoods. These fashionable

districts were rebuilt in time but many of the old residents had moved out to

the suburbs north of Pasig, away from the direction of Makati. Unless there was a plan for Makati, the

hacienda would be hemmed in by slums and its land values placed in serious

jeopardy.

Jimmy joined Ayala y Compania (now Ayala Corporation) in 1951,

with some concern about leaving the military life he knew so well, and joining

the business world he knew little about.

He used to say that military life was easier in that all one had to do

was follows rules and regulations. Even

one’s relationships with your superiors and peers were guided by one’s

rank. But the war was now over, and

there was not much future for his talents and training in military planning,

command, and ground staff administration, where he had spent most of his 25

adult years. He was 44, had 2 children,

with another on the way. He had to find

his future in the business world, somewhere where his ability as a planner

could best be used.

Colonel Joseph McMicking, U.S. Army

- retired, had married into the Ayala

family, and was involved in the development of Hacienda Makati. Integrated urban planning was not new in the

United States, but most Manilans had to be convinced. The development of Hacienda Makati was moving along very very

slowly. In 1951, he sought out a

comrade, Colonel Jaime C. Velasquez, a fellow military man who, like himself,

understood the far reaching benefits of military planning.

Jimmy Velasquez and Joe McMicking

eventually struck up an affectionate and bantering partnership that was able to

accomplish what everybody thought could not be done: develop Hacienda Makati into a modern, multi-zoned subcity to be

built in stages over 25 years, each zone complementing and enhancing the value

of the others. There is no anecdote of

how the two had met, or how the latter had learned of the former, leading to

that fateful call. We may surmise that

Manila was a much smaller place then, with the colonial military network

contributing its own valuable share to their summit. Their names could have rung familiar to each other as nearly as

the wake of General Douglas MacArthur and President Manuel L. Quezon’s exodus

to Australia in mid-1942. The

Filipino-Scottish McMicking was in the beleaguered General’s departing squadron

as an intelligence officer. Velasquez,

on the other hand, was one of the President’s illustrious retinue of

aides-de-camp, a Chief-of-Staff of the 91st PA Division of the

Philippine Constabulary and a battalion commander of the 1st

Filipino Regiment in the US Army. It is

known that Velasquez was active for the better part of the war years in

Australia with MacArthur’s USAFFE (United States Armed Forces in the Far East).

By the time Jaime C. Velasquez

accepted the job as Administrator of Hacienda Makati, hundreds of homeless

families had settled illegally in the property. With the additional tenants who cultivated the farms in the area,

they had to be relocated. To meet this

social program squarely, and to eliminate any possible social unrest, special

villages were created within the hacienda where lots were sold inexpensively at

very liberal terms. Industries were

also brought in to provide livelihood.

Attracting the affluent to transfer their homes to Makati was not easy,

and inducements had to be offered.

Velasquez launched a vigorous

campaign to visit promising entrepreneurs and offer ready advise. Those who lent him an ear never regretted

his visits. Two Filipino-Chinese

businessmen who heeded his advise, Henry Ng (who operated a grocery at Isaac

Peral Street in Ermita’s expatriate neighborhood) and Henry Sy (who owned a

shoe store in Rizal Avenue in downtown Manila) have since become luminaries in

the Philippine business community, beginning with the Makati Supermarket and ShoeMart, respectively, at the then

Ayala Center. Many others have similarly benefited from Velasquez’s

prodding. He went on to become the key

figure in Ayala’s day-to-day operations, piecing together the formula for the

development of a planned complex where commerce and residence would thrive in a

balanced environment.

Velasquez succeeded in convincing

Manila’s rich to purchase lots in Forbes Park, which opened in 1949. More subdivisions sprang up and lots sold

quickly – San Lorenzo in 1952, Bel Air in 1954, Urdaneta in 1957, San Miguel in

1960, Magallanes and Dasmarinas in 1962.

One of the rare times he was quoted publicly was in 1961, when he

remarked, “It’s been a seller’s market ever since, and we’d like to keep it

that way.”

As word spread that Makati was the

place to buy land, Ayala Avenue – a six-lane boulevard through the heart of

Makati where high-rise buildings form a financial hub – rose to prominence. The avenue, formerly the Nielsen Airfield

which functioned as a landing strip for military planes, had been transformed

into the most prestigious thoroughfare in the country. The Ayala Center, the Philippines’ fully

integrated commercial complex, was another of Velasquez’s projects as its chief

zone planner. He visualized it as “the

jewel in the crown”. The early Center

was a marvel of its day, replete with conveniences and modern features which

Filipino locals merely saw in American films.

Today, the Center is the premier showcase of shopping center design as

well as innovations in marketing concepts.

Today’s huge malls such as the Glorieta and the Greenbelt Mall, large

multi-departmental stores such as ShoeMart and Landmark, and first class hotels

such as New World, Shangri La, Peninsula, Mandarin, InterContinental, and

Oakwood are a testament to Jimmy’s vision of a commercial and residential

complex thriving in a balanced environment.

Through all this work at Ayala,

Jimmy continued to distinguish himself in public service, on loan to the

Philippine government from time to time from Ayala y Compania from 1954 to

1960. At various times during this

period Jimmy served as Commissioner of Customs, as a member of the Reparations

Survey Mission to Japan, and as a member of the Monetary Board of the Central

Bank of the Philippines. His stint as

Commissioner of Customs deserves emulation as he managed to eradicate

corruption down to the lowest clerk.

In 1964, Jimmy was appointed a

Director of Ayala y Compania, and Vice-president

and Director of the Ayala Securities Corporation, staying on until his

retirement in 1967, the year before Ayala y Compania was incorporated. Subsequently he became Chairman of the Board

of the Ayala Investment and Development Corporation in 1969, and then Chairman

of the Board of the Bank of the Philippine Islands in 1973. In the same year, he was named Consultant to

the Ayala Corporation.

RETIREMENT

Since his retirement, he became involved with other business activities

such as the Bank of Asia and the FGU Insurance Corporation, where he was a

director in both institutions. He

involved himself in civic endeavors, becoming trustee for three terms of both

the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation and the Filipinas Foundation (now the Ayala Foundation).

In his heyday, old hands at Ayala

remember Jaime Velasquez as a man of character and of the highest

integrity. His colorful and sharp wit

preyed on all at Ayala, including the young dons of the Ayala family. When agitated, his voice would resound

through the office walls down the corridor in his distinctive Bulakeño accent

as the staff held on to their seats. A

stickler for detail and accuracy, his office memos, sprinkled with military

terms, were structured with nested subsections and subclauses. More than that, he was like the proverbial

schoolmaster, stern yet possessed of a gentle heart.

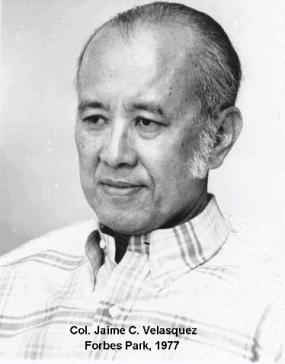

One of the last pictures of Jimmy, taken at his Forbes

Park home, summer of 1977

His long and faithful service to his

country in both public and private endeavors was characterized by jobs well

done, which remained consistently through the years in keeping with the highest tradition of “Duty, honor, and

country”. Jimmy’s decorations include a

Silver Star, Legion of Merit, and Commendation Ribbon from the U.S. Government,

and Distinguished Service Star with Oak Leaf Cluster from the Philippine

Government. He was a man of action as

well as ideals, a visionary who drew a master plan with Joe McMicking and

harnessed it to reality. With his

passing on October 5, 1979 at the age of 72, Jimmy had spent a lifetime as one

who had stood at various crossroads of history, at times a witness, and then as

a trailblazer. The solace of his

remaining years were in the comfort of family and home, dabbling in culinary

experiments, keeping up with events in the Philippines and in the world, and

friendly games of poker with the closest of friends.

-Tisa Velasquez Fernandez

Sources --------------------------------------------------------------------

Write-up by Juan H. Alegre III,

August 1993.

Baliwag.

Then and Now, by Rolando E. Villacorte, 1970

History of the Filipino People, by Agoncillo &

Guerrero, 1987

Velasquez

Family Archives

NOTE: This entire document can be viewed on the

internet at:

http://jaimecvelasquez.bizland.com